Native students at boarding schools found outlets for fun and, in some cases, felt a

continuance of their own cultural practices in unexpected places where they could participate in,

outside of the regular school curriculum. Extracurricular activities are important for the

development of a child’s social and creative abilities, but also act as an escape from the reality of

their daily life. In many cases, Native students faced physical, sexual, emotional, and spiritual

abuse, neglect, and malnutrition in the schools, which picked at their spirit daily. These outlets of

escape allowed a break from the harsh cruelties and made it possible for students to find hope for their future and a chance to stand out.

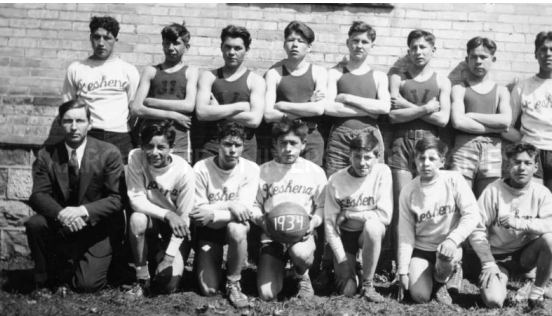

When available, sports were a popular pastime among the students, and the school priests

and nuns usually encouraged it as well. Lacrosse, of Native origin, was discouraged. Yet, the

seasons for “American” sports such as basketball and football were highly spoken about

throughout the school; the priests communicated via letters about the promising and

exciting season ahead. Although the male population dominated the sports realm in most cases,

some schools offered sports such as basketball to the female youth as well. For instance, in the

early 20th century, the Fort Shaw Indian school women’s basketball team held a strong reign in

the public eye of female sports. Although the team faced inevitable prejudices against Natives

from opposing teams and fans, the team remained an insurmountable force, having led their

7-person squad to an undefeated record in 1904. As one report from the Anaconda Standard

notes, “There is no team in the state that can give them anything like a tussle. They stand alone

and unrivaled. This may not be [pleasant] reading for the white girls…but it is true.” 1 The

renowned victories of the 1904 Fort Shaw Indian school’s women’s basketball team would leave

a strong historical mark on the representation of Native women in sports and the integrity of

Native boarding school students to stand up to the oppressors through their own form of

expression.

The school administration also organized theater productions for the students to partake

in, where they further assimilated Native children into the Christian teachings and historical

plays, but it also let the students express themselves through acting and costumes. In the St.

Mary’s Indian school newspaper article from 1949, the author describes the production the

students are putting on for the 95th anniversary of the signing of the treaty of 1854 by the

Odanah Indians. Whilst explaining the significance of the play from the perspective of the

non-Native administration, the writer states that “the climax was the attack on the white men’s

fort, and the burning of the stockade, and the massacre of the whites.”2 This directly proves the

school’s intent on forming a negative resonance with the Natives for the children to grasp and

view the white men as the positive outtake. Furthermore, the students would act in plays that

originated from Catholic traditions such as holidays dedicated to popular Christian saints or traditions commonly followed in Christianity and other denominations. As a form of playtime,

children would dress in costumes of primarily white figures or act as part of a Christian tradition

such as a wedding. This form of matrimonial play reinforces Western and Christian gender and

marital norms, even as it is a form of play.

Gallery

“Odanah Indians Celebrate Signing of 1854 Treaty.” 1949. Series 1-1, Box 287, Folder 4. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI.

This document describes that the Odanah Peoples were celebrating the 1854 Treaty signing with the United States government. The 1854 Treaty stated that the Chippewa ceded to the United States ownership of their lands in northeastern Minnesota. It is confusing then as to why this massive loss of lands would have been celebrated. It begs the question as to the point of view from which the letter was written and how documents like this played a role in propaganda around the feelings of Indigenous Peoples to the loss of their land

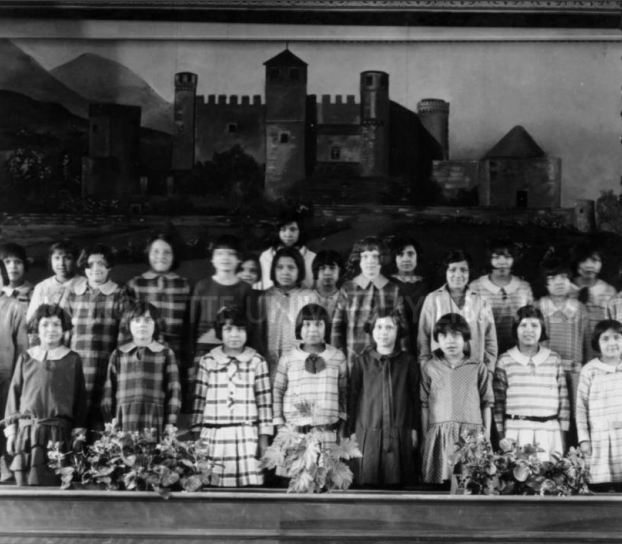

Cast of school play, 1930. 1930. Series 09-1, Box 56, Folder 03. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI.

In this photo of the cast of a school play, one can see the almost uniform short hairstyle, which was required by the schools when Native children arrived. The shorter hair showed a more “civilized” appearance as the boarding school’s administration continued to assimilate the children into white culture. The chopping of a person’s long hair signified great disrespect towards many Native Americans, as long hair is spiritually connected and found to represent strength and power while also keeping them closer to Mother Earth. Chopping of the hair of Native children was highly common in boarding schools as it was the first step in physically stripping the children from their spirituality and culture, while forcing a completely foreign and unwanted belief system onto them instead. The

young girls wear popular clothing in the photo, mainstream dresses and skirts worn by children during the 1930s. The name of the play that the girls are participating in is called “Father’s Day Feast Party,” which is an annual Catholic celebration celebrated in European countries, also known as “St. Joseph’s Day.” This holiday originated in the Middle Ages, which directly correlates to the stage’s setting in the background in the photo.

Young Menominee girls at play, undated. Series 9-1, Box 56, Folder 5. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI.

St. Joseph’s Indian School basketball team, 1934. 1934. Series 9-1, Box 56, Folder 3. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI.

Seen here is the 1934 St. Joseph’s Mission school boy’s basketball team. The teams were coached by faculty such as the Brother (unnamed) shown in the front left of the photo. The rest of the team is comprised of students attending St. Joseph’s Mission school out of Keshena, Wisconsin. Notably all the students in the photo have the same short haircut forced upon them since the beginnings of their enrollment at the Indian school, while the loss of long, sacred hair is mourned by many Native tribes who cherished it. The boys are also shown to be dressed in their white and labeled

basketball warmup sweatshirts, while the rest of the team is dressed in the typical 1930’s basketball jersey.

Menominee Indian children enacting wedding, 1931. 1931. Series 09-1, Box 56, Folder 03. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University,

Milwaukee, WI.

The children in this photo are dressed in costumes in order to reenact a typical Christian wedding. The young girl dressed as a bride (front row, 4th from right) is dressed in an all white gown, which represents purity and innocence in Christian teachings. The young boy dressed as a groom (front row, 3rd from the right) wears a traditional suit and tie as most men would in Christian weddings, while holding the arm of his spouse for the photo. To the right of the groom stands a boy dressed as the officiant of the wedding in a typical outfit of a priest who is traditionally the officiants of a Catholic wedding.

Document Translations

“Odanah Indians Celebrate Signing of 1854 Treaty.”

The 95th anniversary of the Treaty of 1854 between the Chippewa Indians and the United

States government was celebrated October first and second by the Bad River band of Chippewas

in a three-day pageant and a series of dances.

Various aspects of Chippewa life and customs, from ancient times down through the

arrival of the first [French] fur-traders, and to the signing of the treaty in 1854 were depicted in

dramatic [t]ableaux and dances. The climax was the attack on the white men’s fort, and the

burning of the stockade, and the massacre of the whites.

About thirty-five meant [sic], women, boys and girls, comprised the cast. The role of

[Chief] Black Cloud was taken by the Chief Jacco, leader of the Odanah band of dancers.

Angeline Cedarroot, 89 years of age, in an active dancer of the group.

The enclosed snap shows two of the smallest borders of St. Mary’s Indian School,

Odanah, Wis.