Reservation Day Schools

Reservation Day Schools were the first type of school created to begin the conversion project:

“Located on the outskirts of Indian villages, day schools served as the educational outposts of

civilization. By the 1860s, forty-eight such schools were in existence. The theory behind this

approach was that in the early-morning hours children would pour forth from the nearby Indian camp and at day’s end return to their homes wiser in the ways of white civilization.” 1 “Efforts to

raise up the child during school hours, it was argued, were obliterated at night by the realities of

camp life,”2 and so policymakers, government officials, and religious entities concluded that

reservation day schools were not an effective model of assimilation because of their proximity to

the student’s communities, parents, and ways of life.

On-Reservation Boarding Schools

A new form of school emerged as a solution to the children’s proximity of the reservation day

school to tribal communities–on-reservation Boarding Schools. The boarding aspect of the

school was a concept that prevented students from contact with their families, and “the chief

advantage of the boarding school was that it established greater institutional control over the

children’s lives, with students being kept in school eight to nine months out of the year.”3 Some

survivors have used the term “incarceration” to describe their boarding school experiences.

Incarceration denotes the control and confinement of children, and “in any case, sustained

confinement was now deemed to be the key element in the civilization process.”4

Off-Reservation Boarding Schools

The conclusive method for the most effective form of schooling for government officials and

religious organizations was off-reservation boarding schools. The idea was to remove children

from their families and send them far away, at times thousands of miles away across the country,

to attend school and prevent familial and tribal contact to strip Indigenous children of any

Indigenous culture and identity. For example, “From 1879 through the late 1930s, thousands of

Ojibwe, Dakota, Menominee, Oneida, and other tribal children from Minnesota, Wisconsin, and

the Dakotas traveled far away to receive a government education.”5 In some instances, the schools served as a refuge from starvation and poverty experienced within the reservation system, a result of removal and governmental policy. The schools purported to provide basic needs for students such as food, shelter, and clothing. The fulfillment of this promise to meet students’ basic needs varies according to school and time period. In 1891, Congress passes a law that required Native American children to attend school.

Gallery

See Samples from MU’s BCIM correspondence archives below:

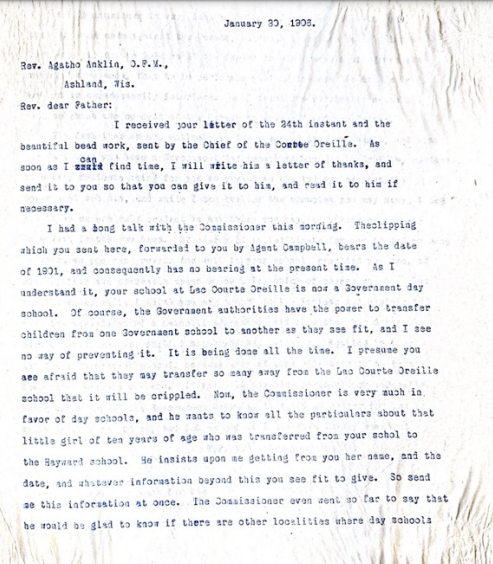

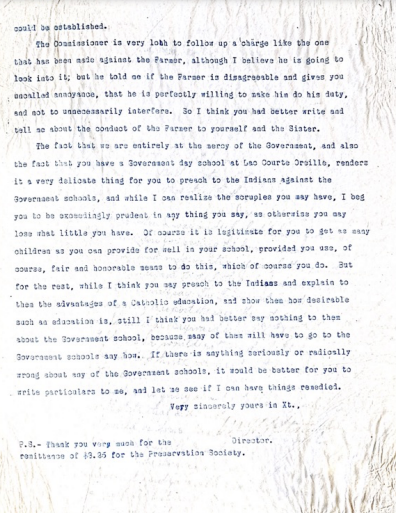

Ketcham, William Henry. “Letter to Agatho Anklin.” 1906. Series 1-1, Box 54, Folder 11. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI.

The following letter shows competition between the government schools and the Catholic schools

to secure Native students as well as the strategies to persuade Native parents to send their

children to Catholic schools.

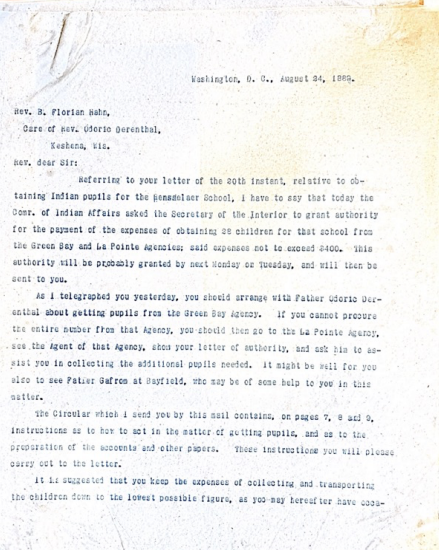

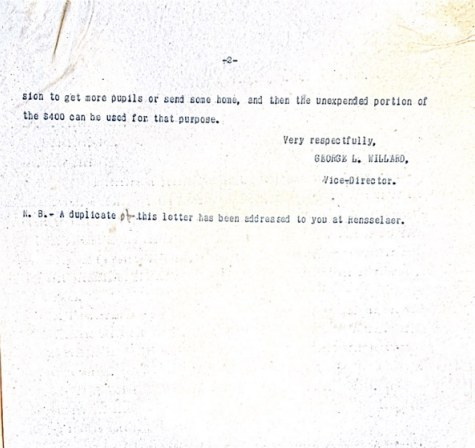

Willard, George L. “Letter to Reverend B. Florian Hahn from Vice-Director of Bureau of Indian Affairs.” Series 1-1, Box 24, Folder 17. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI.

This document shows how “obtaining” pupils for the various schools seemed very transactional

in their “collecting and transporting” of the children. Schools needed students in order to sustain operations so they traveled to various Native communities in order to meet their student quotas. The letter mentioned the Secretary of the Interior which suggests a relationship between the Catholic church and the United States government in this project.

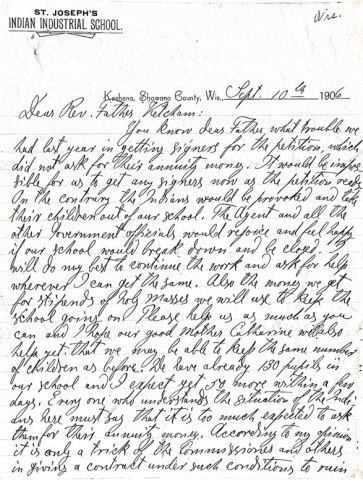

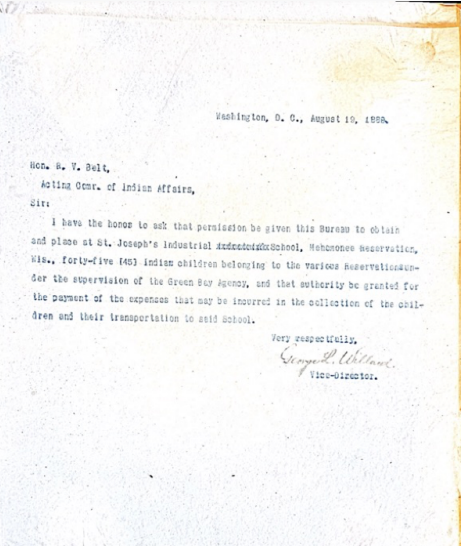

Krake, Blase. “Letter from Father. Blase Krake to Director William Henry Ketcham.” 1906. Series 1-1, Box 55, Folder 14. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI.

This letter shows clear competition between the government schools and the Catholic schools in

vying for Native children to attend. There are accusations made that the government was attempting to sabotage Catholic schools in order to have Native children attend their schools

instead. Additionally, the letter details the ideas around having Native parents use their annuity

money to pay for their children to attend these schools. Annuity payments were a sum of money

that the United States Government pay to Native Peoples in return for the selling of their lands.

In many instances, Native parents were required to pay for their own children to attend schools

even though they had no other options but to send their children. There was a lot of politics at

play and Native students and families were stuck in the middle.

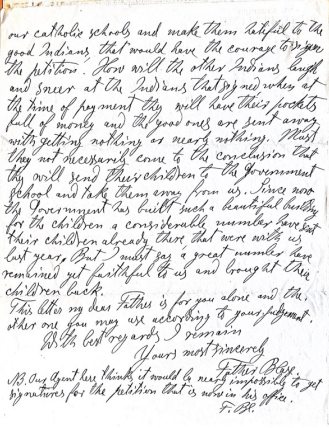

Willard, George L. “Letter to Robert V. Belt, Commander of Indian Affairs from Vice-Director of Bureau of Indian Affairs.” 1889. Series 1-1, Box 24, Folder 17. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI.

This correspondence document shows that Native children were removed from their homes and communities and taken to schools away from their families.

Priests, religious sisters, and Ojibwa elder, 1928. 1928. Series 9-1, Box 56, Folder 2. Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions Records. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI.

Document Translations

Ketcham, William Henry. “Letter to Agatho Anilin.”

Rev. Agatho Anklin, O.F.M.,

Ashland, Wis.

Rec. dear Father:

I received your letter of the 24th instant and the beautiful bead work, sent by the Chief of

the Courte Oreille. As soon as I can find time, I will write him a letter of thanks, and send it to

you so that you can give it to him, and read it to him if necessary.

I had a long talk with the Commissioner this morning. The clipping which you sent here,

forwarded to you by Agent Campbell, bears the date of 1901, and consequently has no bearing at the present time. As I understand it, your school at Lac Course Oreille is now a Government day school. Of course the Government authorities have the power to transfer children from one Government school to another as they see fit, and I see no way of preventing it. It is being done all the time. I presume you are afraid that they may transfer so many away from the Lac Courte Oreille school that it will be crippled. Now, the commissioner is very much in favor of day

schools, and he wants to know all the particulars about that little girl of ten years of age who was transferred from your school to the Hayward school. He insists upon me getting from you her name, and the date, and whatever information beyond this you see fit to give. So send [illegible] this information at once. The commissioner even went so far as to say that he would be glad to know if there are other localities where day schools could be established.

The commissioner is very loath to follow up a charge like this one that has been made

agains the Farmer, although I believe he is going to look into it; but he told me if the Farmer is

disagreeable and gives uncalled annoyance, that he is perfectly willing to make him do his duty, and not to unnecessarily interfere. So I think you had better write and tell so about the conduct of the Farmer to yourself and the Sister.

The fact that we are entirely at the mercy of the Government, and also the fact that you

have a Government day school at Lac Courte Oreille, renders it a very delicate thing for you to

preach to the Indians against the Government schools, and while I can realize the scruples you

may have, I beg you to be exceedingly prudent in any thing you say, as otherwise you may lose

what little you have. Of course it is legitimate for you to get as many children as you can provide

for well in your school, provided you use, of course, fair and honorable means to do this, which you of course do. But for the rest, while I think you many preach to the Indians and explain to them the advantages of a Catholic education, and show them how desirable such an education is, still I think you had better say nothing to them about the Government school, because many of them will have to go to the Government school any how. If there is anything seriously or radically wrong about any of the Government schools, it would be better for you to write particulars to me, and let me see if I can have things remedied.

Very sincerely yours in XT.,

P.S. Thank you very much for the remittance of $3.25 for the Preservation Society Director William Henry Ketcham

Willard, George L. “Letter to Robert V. Belt…”

Hon. R.V. Belt,

Acting Comr. of Indian Affairs,

Sir:

I have the honor to ask that permission be given this Bureau to obtain and place at St. Joseph’s Industrial School, Menomonee Reservation, Wis., forty-five (45) Indian children belonging to the various Reservations under the supervision of the Green Bay Agency, and that authority be granted for the payment of the expenses that may be incurred in the collection of the children and their transportation to said school.

Very respectfully,

George L. Willard

Vice-Director

Willard, George L. “Letter to Reverend B. Florian Hahn…”

Rev. B. Florian Hahn

Care of Rev. Odoric Derenthal,

Keshena, Wis.

Rev. dear Sir:

Referring to your letter of the 20th instant, relative to obtaining Indian pupils from the

Rensselaer School, I have to say that today the Comr. of Indian Affairs asked the Secretary of the Interior to grant authority for the payment of the expenses of obtaining 28 children for that

school from the Green Bay and La Pointe Agencies; said expenses not to exceed $400. This authority will be probably granted by next Monday or Tuesday, and will then be sent to you.

As I telegraphed you yesterday, you should arrange with Father Odoric Derenthal about

getting pupils from the Green Bay Agency. If you cannot procure the entire number from that

Agency, you should then go to the La Pointe Agency, see the Agent of that Agency, show your letter of authority, and ask him to assist you in collecting the additional pupils needed. It might be well for you to also see Father Gafrom at Bayfield, who may be of some help to you in this matter.

The Circular which I send you by this mail contains, on page 7, 8 and 9, instructions as to

how to act in the matter of getting pupils, and as to the preparation of the accounts and other

papers. These instructions you will please carry out to the letter.

It is suggested that you keep the expenses of collecting and transporting the children

down to the lowest possible figure, as you may hereafter have occasion to get more pupils or

send some home, and then the unexpected portion of the $400 can be used for that purpose.

Very respectfully, George L. Willard,

Vice-Director.

N.B. A duplicate of this letter had been addressed to you at Rensselaer.

Krake, Blase. “Letter from Father. Blase Krake to Director William Henry Ketcham.”

Dear Rev. Father Ketcham:

You know dear Father what trouble we had last year in getting signers for the petition,

which did not ask for their annuity money. It would be impossible for us to get any signers now as the petition reads. On the contrary the Indians would be provoked and take their children out of school. The Agent and all the other Government officials would rejoice and feel happy if our school would break down and be closed. I will do my best to continue the work and ask for help wherever I can get the same. Also the money we get for stipends of holy masses we will use to keep the school going on. Please help us as much as you can and I hope good mother Catharine will also help yet. That we may be able to keep the same number of children as before. We have already 130 pupils in our school and I expect yet [30 or 50] more within a few days. Everyone who understands the situation of the Indians here must say that it is too much expected to ask them for their annuity money. According to my opinion it is only a trick of the Commissioners and others in giving a contract under such conditions to ruin our Catholic schools and make them hateful to the good Indians, that would have the courage to sign the petition. How will the other Indians laugh and sneer at the Indians that signed when at the time of payment they will have their pockets full of money and the good ones are sent away with getting nothing or nearly nothing. Must not necessarily come to the conclusion that they will send their children to the government school and take them away from us. Since now the Government has built such a beautiful building for the children a considerable number have sent their children already there, that were with us last year, But I must say a great number have remained yet faithful to us and brought their children back.

This letter my dear Father is for you alone and the other one you may use according to

your judgement.

With the best regard I remain

Yours most sincerely,

Father Blasé

B. Our agent here thinks it would be nearly impossible to get signatures for the petition that is word in his office.

F.Bl.

- David Wallace Adams, “Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School

Experience, 1875-1928” (University Press of Kansas, 2020) 33. ↩︎ - David Wallace Adams, “Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School

Experience, 1875-1928” (University Press of Kansas, 2020) 34. ↩︎ - David Wallace Adams, “Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School

Experience, 1875-1928” (University Press of Kansas, 2020) 36. ↩︎ - David Wallace Adams, “Education for Extinction: American Indians and the Boarding School

Experience, 1875-1928” (University Press of Kansas, 2020) 36. ↩︎ - Child, Brenda J. “Boarding School Seasons: American Indian Families, 1900-1940” (University of Nebraska Press, 2000) 44. ↩︎